Cloud Computing, What Is It Good For?

This is a soft guide to cloud computing for creative coders who want to deploy open-weight models in a cost and energy efficient way; or for anyone who might be curious about basic concepts of cloud computing. Written in Tom Igoe's Understanding Networks course at ITP NYU.

Whether you've fine-tuned your own image generation model, running data analysis, or prefer to use an open-weight LLM to preserve your data autonomy and privacy, there are plenty of reasons for creative coders and small scale developers to use GPUs. The issue is that long-term monthly subscriptions to GPU services could cost hundreds of dollars and if your app only gets a couple of visitors a week, that is a lot of money for a lot of idle GPU time.

This is the essential benefit of cloud computing for both small scale developers and enterprise alike - renting hardware from providers on a pay-per-compute model that elastically expands and shrinks according to your needs. Think Citi Bike. You don't buy your own bike, you only pay-per-ride-time, and once you're done you lock the bike and forget about it.

This isn't only an efficient business model and potentially efficient way to manage energy consumption (sharing is caring), it also solves the classic "but the code worked on my machine" problem. Instead of building software that is dependent on a specific machines operating system and dependencies, programs can run across any machine on the network thanks to techniques called virtualization and containerization. These techniques allow software to encapsulate its environment, so each application runs in a clean, isolated space.

Machines

Hardware moves electrons around with silicon, plastic, and metals to create memory, compute, cooling, and light.

Kernel the part of the operating system which bridges applications to the hardware with drivers. Schedules CPU processes, makes sure memory isn't overwritten etc.

User space the part of the operating system which holds the applications. This includes everything from shell to runtimes, dependencies, and scripts.

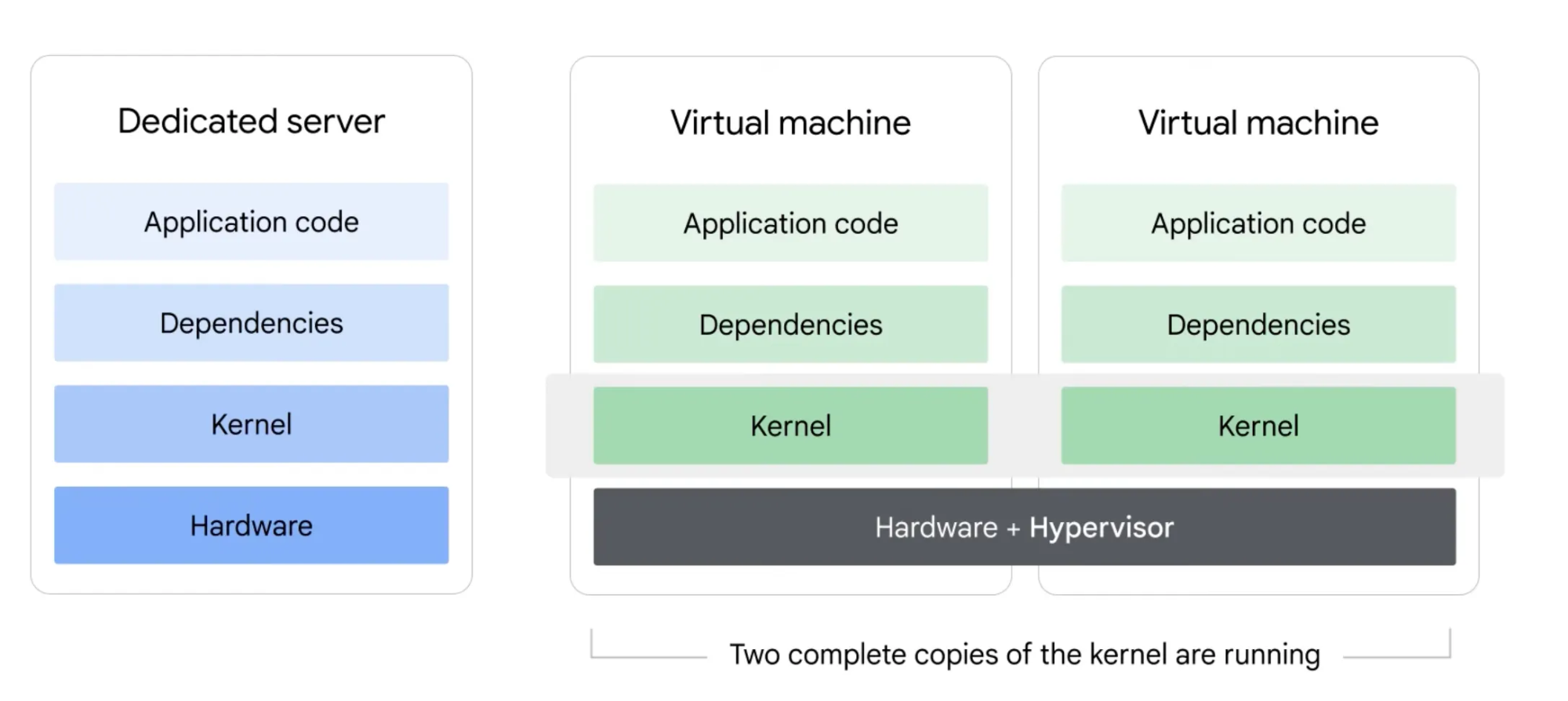

Virtual Machines

A computing technique that adds a layer between the kernel and user space called the hypervisor, which creates multiple virtual machines complete with their own kernel and user space on a single hardware stack.

Hypervisor mediates between multiple kernels and the hardware, allowing multiple encapsulated kernels to run on the same machine.

Virtual machines solve the problem of conflicting dependencies and incompatible operating systems; but installing a new kernel is actually installing a new operating system for every application running on the machine. This is a waste of time and resources, and slows down scaling.

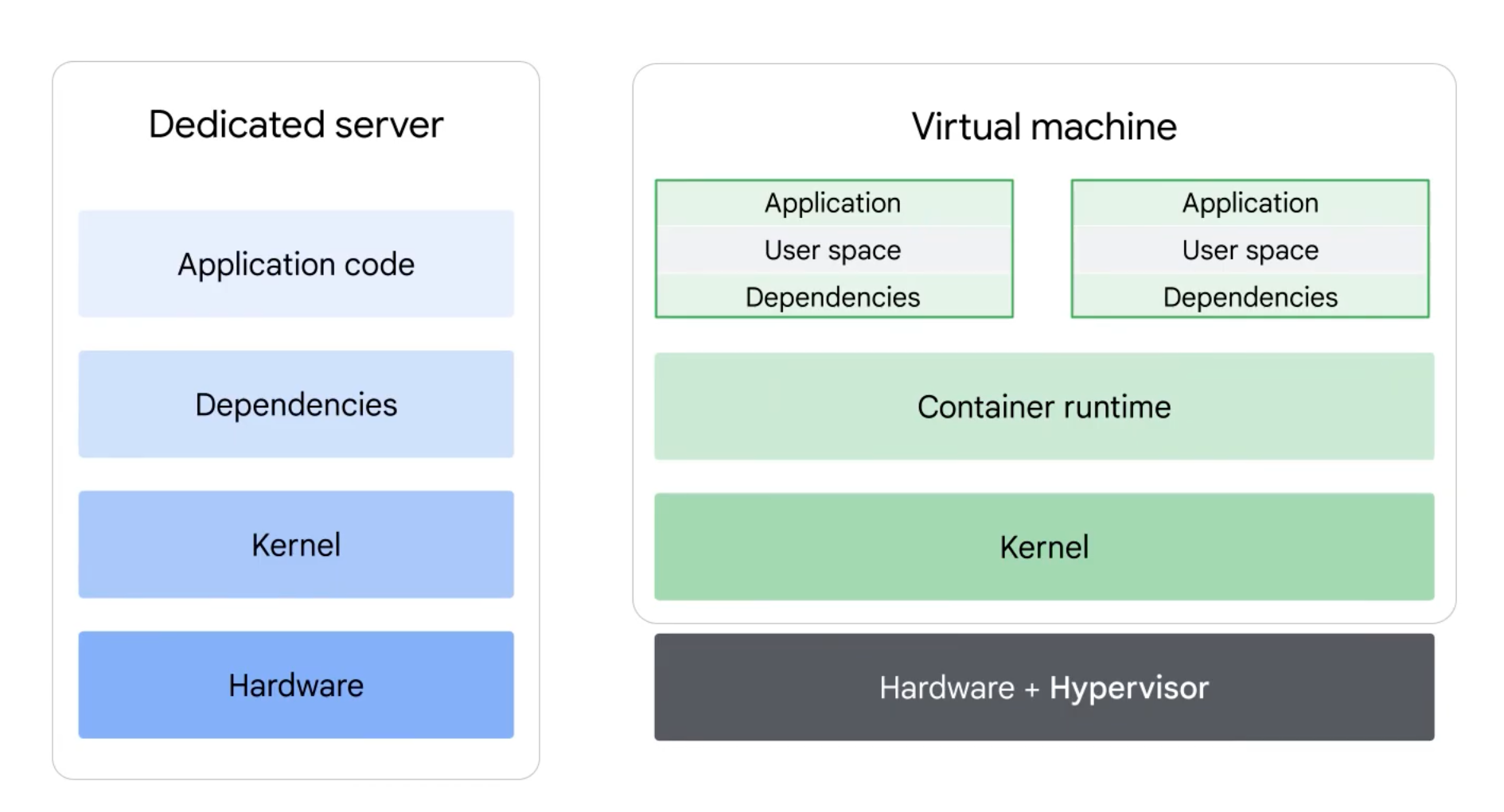

Containers

To bypass the need for multiple kernels on a virtual machine another layer of encapsulation is applied above the kernel, allowing each machine to run a single hypervisor and operating system, with encapsulated environments for each application. So instead of encapsulating whole kernels, containerization only encapsulates the user space. This allows avoiding incompatibility and dependency conflicts without multiplying heavy kernels for each app.

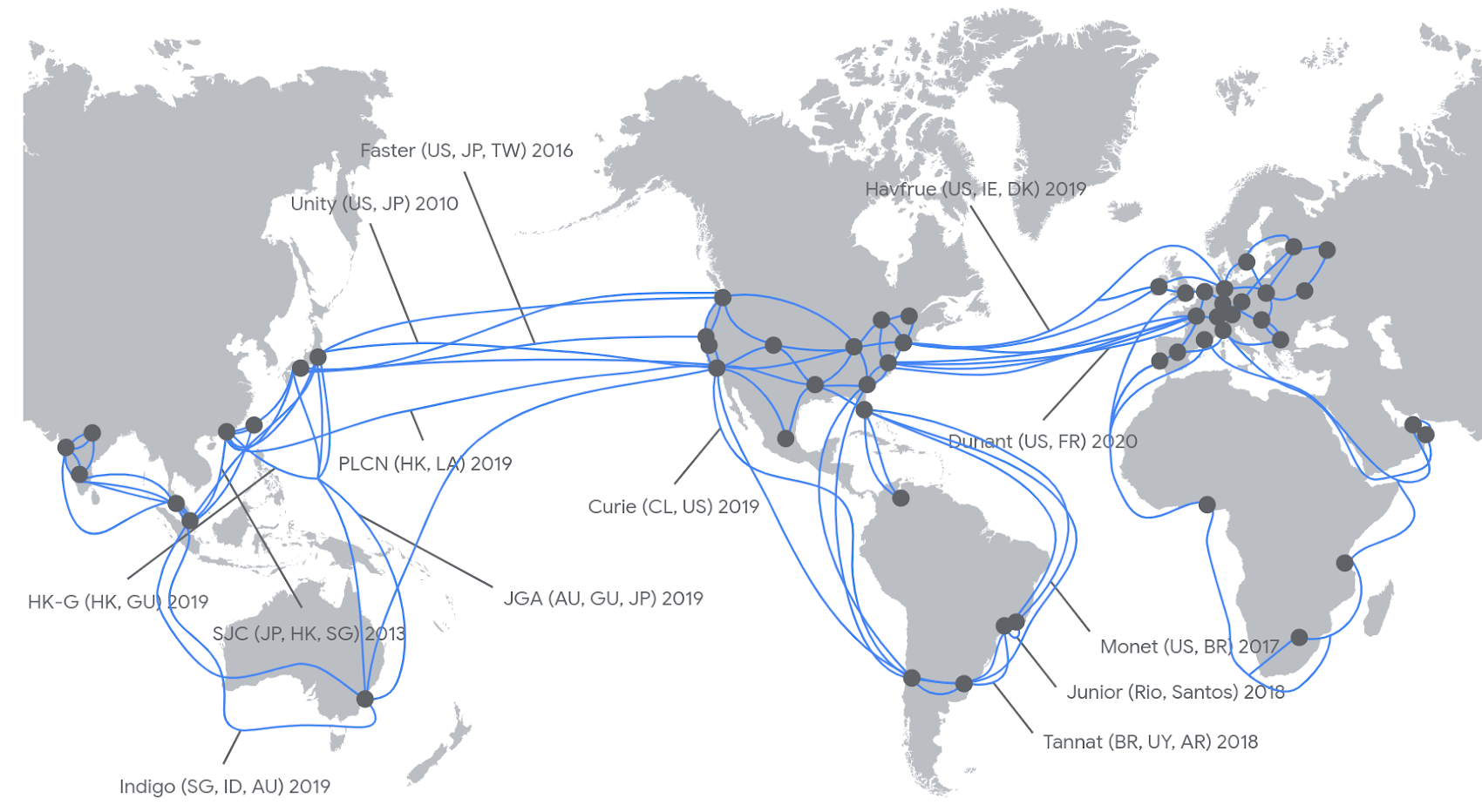

Containerization allows the web applications we use everyday to run on flexible global networks of compute clusters. The flexibility of these networks means they rise and ebb according to demand. Containers are built with tools like Docker, which include instructions for installing the runtime dependencies your app needs before it starts. This set of instructions is called an image: a blueprint that becomes a running container when deployed. But that's a topic for another guide.

This (honestly) monumental technological achievement requires a competent orchestrator to enable efficient resource allocation, and it is called Kubernetes. Luckily, unless you are running some serious enterprise software, you likely don't need to manually configure your own Kubernetes orchestration. Large cloud providers offer services that automate most of the tough parts and abstract it all into a comfortable (relatively) graphical interface. There are also smaller companies that further simplify the use of cloud resources.

Clusters, Nodes, Pods

The following are descriptions of the basic parts that make up a virtual computing network. For most use cases in ITP you probably won't have to deal with them and can deploy your applet using a GPU runtime service that simplifies the process, but if you've made it this far, why stop now?

Clusters

Clusters are the foundational unit of Kubernetes, made up of virtual machines with different hardware configurations (CPUs, GPUs, memory). Each cluster has a control plane that schedules and orchestrates its different components.

Nodes

Nodes are individual virtual machines within a cluster. Each node can be configured with specific hardware. For example, a GPU node would have a particular type of GPU. Nodes scale horizontally by adding more instances of the same type of compute (e.g., adding more GPU nodes with the same GPU configuration).

Pods

Pods are the smallest deployable units in Kubernetes. Each pod wraps one or more containers that share networking and storage. Multiple pods run on each node, and they're created and destroyed dynamically based on demand. When demand increases, they are "scaled horizontally" which means new instances of the pod are cloned rather than adding more compute to existing pods.

Not So Cold Starts

Now that you know the ropes, you might be wondering how to actually share that app running your fine-tuned model with the world. Luckily there are services that make deploying code easy and allow you to scale to zero, meaning you don't pay for idle GPU time, and the container spins back up when someone hits your endpoint.

Modal stands out here: it lets you define infrastructure directly in your Python script, and offers sub-second cold starts compared to the 2+ minutes(!) you'd wait on Google Cloud Run. This is a short example of how to set up an inference endpoint.

Code Example

- Create account at modal.com

- pip install modal

- modal setup (authenticates your CLI)

- Run the following script with modal deploy app.py. This will log the endpoint's URL, which you can call from your app.

import modal

# Name your app

app = modal.App("my-service")

# Mount volume

volume = modal.Volume.from_name("my-models", create_if_missing=True)

# Choose container image

image = modal.Image.debian_slim().pip_install("torch", "transformers")

# Choose GPU

gpu = "A100"

# Configure container: image, GPU, and mounted storage

@app.cls(image=image, gpu=gpu, volumes={"/models": volume})

class MyEndpoint:

# Runs once when container starts

@modal.enter()

def setup(self):

from transformers import AutoModel

self.model = AutoModel.from_pretrained("/models/my-model")

# HTTP POST endpoint

@modal.web_endpoint(method="POST")

def predict(self, text: str):

return self.model.predict(text)Recap

Open-weight models offer more flexibility and privacy than proprietary AI services, but the complexity of configuring infrastructure and the cost of compute can be serious barriers for deploying creative projects. Luckily, services are helping developers overcome these barriers with smoother, more cost-efficient workflows. Finally, clouds are confusing metaphors. They are not soft ephemeral shapes drifting through the world, rather a massive complex network for hardware for hire. This network has vast social and and environmental consequences, some still unknown.